The NCAA has always grappled with technology and how it affects recruitment. As the world becomes smaller with every technological advance, antiquated NCAA bylaws become a joke to try to enforce as written.

The NCAA has always grappled with technology and how it affects recruitment. As the world becomes smaller with every technological advance, antiquated NCAA bylaws become a joke to try to enforce as written.

I should explain up front that I personally follow a number of Kansas basketball and football recruits on my twitter account, @JayhawkTalk. I even interact with them from time to time. The substance of this interaction can be anything from a “retweet” of what they say (E.g., if a potential recruit tweets something like “I am going to have my in-home visit with Kansas Coach Bill Self this Monday. Can’t wait,” it would get retweeted by a ton of KU fans) to a simple suggestion or nudge that KU is a great place to be.

There has been quite a bit of discussion of late as to what kind of interaction I am allowed to have with recruits, if any. Is “following” them violative of NCAA bylaws? What about mentioning and interacting with them? What if they reach out to me first asking for feedback?

I wanted to spend some time researching these issues so that I could become more knowledgeable about what is allowed, not allowed, and everything in between. I wanted to share this with you because I don’t think many understand it very well. I certainly did not.

I should also add that while I am an attorney, I am not writing this to provide any sort of legal advice. This is my own opinion and analysis of what I have found, both in the actual bylaws and how those bylaws are enforced. In other words, should you get a cease and desist letter from a compliance official, take it seriously. Don’t rely solely on this review as the word.

With that out of the way, leggo.

Texting while recruiting

When text messaging became popular around 2005, parents of recruits began to complain to NCAA officials that their mobile phone bills were rising with every text a coach sent. The NCAA made a blanket response by banning texts to recruits completely in 2007.

When asked to comment about the texting ban (which had just gone into force), Anna Chappel, then head of the NCAA Division I Student-Athlete Advisory Committee said, “If you don’t stop it now, what roads are you going to have to cross later on?”

She could not have expected at that time that the rise of social media networks would force regulators back to the drawing board only a few short years later.

What to do with Facebook, Twitter

Like texting, it took the NCAA a while to figure out what to do with Twitter and Facebook. When the NCAA became convinced that Facebook private messaging and Twitter direct messages were, for all intents and purposes, just like emails, they decided not to regulate them any different than email (email, like regular mail, is unlimited after a recruit’s junior year, subject to certain restrictions).

To the NCAA, it was much easier to try to mold the ever-changing social media world to its existing rulebooks.

Square peg, round hole comes to mind.

After likening direct messages to emails, the NCAA deemed that posting on the Facebook Wall of a recruit or sending a Twitter reply or mention was just like publicizing a player’s recruitment in the media, which isn’t allowed. Regulators again chose to mold new Internet networking into rules already on the books.

But this strategy would only get the NCAA so far.

Not surprisingly, technology continued to advance. It became apparent that recruits were receiving Facebook and Twitter messages from coaches directly to their phones and mobile devices. Regulators were once again faced with a technological dilemma. Is receiving a Facebook message too much like a text message? Or is it more like an email? Or, worse yet, is it some new blend that would force the NCAA to create new legislation?

Not surprisingly, the NCAA still remained steadfast in adapting technology to its own rules.

It issued bulletins stating that once a coach discovers that a recruit is receiving messages to his or her phone, that coach must cease contact through that medium. Certainly not the easiest rule to police.

As coaches became further disenchanted with texting, phone, and social media rules as written, the NCAA did what the NCAA does best: it threw the issue to a committee. Luckily for coaches, it does finally seem that the NCAA is willing to deregulate some forms of electronic communication, including text messaging.

In January, the NCAA approved a number of wide-ranging changes to the recruiting landscape, including the removal of restrictions on electronic communications, mailings, and even calls. Some coaches haven’t appreciated this new “Wild West” approach to recruiting, most notably those coaches of the Big 10. Regardless, it is a rare step in the direction of common sense for the NCAA. After all, these bylaws are virtually impossible to enforce.

So what does this all mean for fans?

So what does this all mean for fans?

Nearly all decrees and rule changes made by the NCAA regarding electronic communication revolve around the recruitment relationship between coach and player. Very little has been said about what kind of interactions fans and recruits can have through social media. That is probably because to the NCAA, this issue is much more black and white.

Fans and boosters should have no interaction with recruits at all.

Not that it’s stopped anyone. Take Taylor Moseley, for instance. In 2009, Moseley, a North Carolina State freshman, created a Facebook group called “John Wall PLEASE come to NC STATE!!!!” After more than 700 people joined the group, Moseley received a cease and desist letter from the N.C. State compliance department. It became a national story as First Amendment rights activists went to bat for Moseley by speaking out in the media on his behalf.

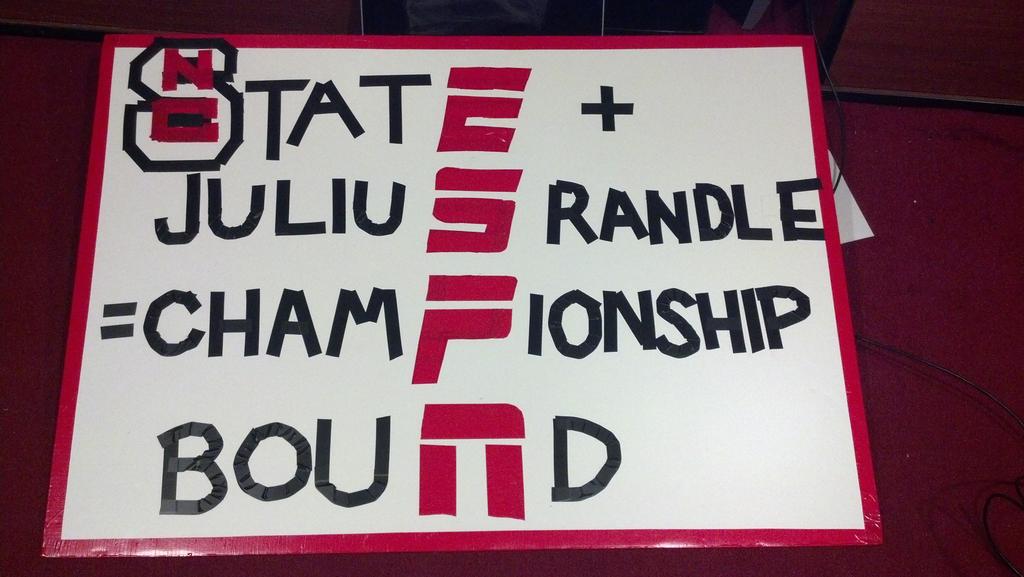

Moseley eventually changed the name of the group. (Not sure if the NC State compliance office confiscated this sign featured on ESPN or this painting done for Julius Randle. I digress.)

It’s important to note that multiple other people created Facebook groups encouraging John Wall to come to their respective school, including students at Baylor, Duke, and at least four groups for Kentucky. There is no indication that the compliance departments at Baylor, Duke, and Kentucky made any such effort to reach out to those students.

What are the schools saying to fans?

What are the schools saying to fans?

We learned two important things from the Moseley fiasco:

First, the NCAA did not ask Moseley to take down the Facebook group or change the name – North Carolina State did. There are very few, if any, reports of the NCAA actually policing individual people from interacting with recruits via social media. That job is tasked to the individual universities, which generally consists of a handful of overworked compliance officers.

Second, compliance departments are not uniform in the way they police interaction among fans and recruits. N.C. State was obviously more proactive in its supervision of students and boosters online. But for every N.C. State department, there are 100 Kentucky departments, which, for one reason or another, do not (or choose not) to police such activity.

Most university compliance departments have a blanket policy on social media on the department website. For instance, North Carolina states the following in one of its bulletins to boosters:

“The use of social networking sites such as Facebook and MySpace can very easily be used by individuals in an attempt to influence prospective student-athletes to attend a specific institution. The NCAA prohibits any involvement by boosters in the recruitment of prospects, and individuals who might initiate these attempts to contact prospects could jeopardize the institution’s ability to continue the recruitment of such prospects.”

Other departments are trying to get more interactive by starting their own Twitter and Facebook accounts. You might see @JayhawkComply on twitter, which recently authored this tweet: “All faculty, staff, students and boosters of KU cannot promote KU in any way or encourage a prospect to attend KU, Leave this to coaches.” In anticipation of Julius Randle’s visit this weekend, it also wrote: “KU Fans: NCAA rules prohibit you from recruiting prospects and publicizing their visit to campus, including signs* in AFH during a game!”

**Speaking of signs, I have heard of KU taking away a sign at a game, but only after the recruit in attendance saw it. In other words, bring your Julius Randle signs to the game. The worst thing that could happen is they take it away. Then just start some Randle chants. Doesn’t hurt.

If you continue to look around at other departments, you’ll see more and more of these vague, blanket, overarching statements loosely referencing the NCAA and it Bylaws. All will have the same basic message: Don’t do it.

Now for the real world.

The reality is that university compliance departments have a lot on their hands. They’re understaffed, they’re overworked, and they simply do not have the resources to track everything on the Internet. They must track athletes already at the university as well as prospective ones. It’s an incredibly difficult task.

Consider this scenario: I create an account called “MUTigerBooster” and start tweeting to potential Missouri recruits to come to Missouri to achieve all the riches in their wildest dreams. I could tell them I’ll provide cars, women, booze, drugs, pizza, STD tests, whatever. All MU could do is tell me to stop. There is no subpoena power. There is no name associated with the account. And it is incredibly unlikely that Twitter would disclose IP addresses or contact information. It is a nightmare for compliance folks.

But what can they do?

**Sidenote: Some university departments are turning to computer programs and outside firms to help police online content from their athletes. One such company is UDiligence, which uses custom keyword lists to catch problems before they occur. For a good time, check out the UDiligence website page where they show images that they have caught. Pretty funny stuff.

I contend that over 99% of the online interaction between fans and recruits will not receive any response from the university the fan represents. Don’t confuse this as tacit approval of the action from the university. It’s not. But policing online content on social media websites would take 100 employees, not 5. That being said, most of the time if a violation is reported to compliance officials, they will look into it and issue a request to stop the behavior if it is found to be violative.

**Another sidenote: I’m sure by writing this piece I will be getting a message the next time I reply to a tweet from Julius Randle or Tyus Jones.

My take

The most interesting part of this whole thing? The recruits want you to tweet them. They want as many followers as they can possibly get, and the attention from a particular school’s fan base does have an effect on what school that guy chooses. To say otherwise is ignorant.

“@kwizz08: @j30_randle making a sign for you for Saturdays game!” Can’t wait !

— Julius Randle (@J30_RANDLE) February 13, 2013

Obviously that also means that coaches secretly want fans tweeting to prospects too. It hammers home the recruiting pitch that if you come to Kansas, you’ll be beloved by all of KU nation – and you can see that’s already happening on your twitter feed. Coaches may come out and say that they don’t need the extra help, but I would argue that they are not being truthful. It doesn’t hurt to have some extra help, especially when every other school is doing it too.

I think there is a competitive advantage in the recruiting game to have a fan base on social networks that follow and interact with recruits. Even though the NCAA and the university compliance department tells me not to, I will continue to follow, retweet, and interact with recruits. And I actually encourage you all to do the same.

Obviously you have to be smart and tactful about it. When tweeting, do so in a classy and respectful manner. And if a player doesn’t choose KU, wish him well and call it a day.

But until I see equal policing across the board from other Division I compliance departments that KU competes with, I will maintain my position on this.

Happy tweeting.

Tags: Basketball, Compliance, ESPN, facebook, Gameday, Kansas, NCAA, Recruiting, Twitter